7. Do Food Miles Matter?

Many students are interested in understanding the impacts that their daily actions have on the environment. Over the last two decades, “food miles”—the distance food travels from farm to plate—has become a frequently cited measure of the consequences of food system choices.1 Sarah DeWeerdt, writing for World Watch magazine, noted its appeal: “The concept offers a kind of convenient shorthand for describing a food system that’s centralized, industrialized, and complex almost to the point of absurdity. And, since our food is transported all those miles in ships, trucks, and planes, attention to food miles links up with broader concerns about the emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases from fossil-fueled transport.”2

Much of the interest in food miles in the US dates to a 2001 study led by Rich Pirog, associate director of the Leopold Center for Sustainable Agriculture at Iowa State University. Pirog and his associates analyzed fruits and vegetables shipped through local, regional, and conventional food distribution systems to Iowa markets. They calculated that produce in the conventional system (a national network using semitrailer trucks to haul food to large grocery stores) traveled an average of 1,518 miles, while locally sourced food traveled an average of 44.6 miles to Iowa markets.

Systems Perspective: Food miles are clearly an important metric, right? It’s a little more complicated if you look at the whole food system. “Food-miles are a great metaphor for looking at the localness of food, the contrast between local and global food, a way people can get an idea of where their food is coming from,” Pirog told a reporter. However, “They are not a reliable indicator of environmental impact. What one would want to do is look at your carbon footprint across a whole food supply chain.” 3

When encountering “average miles traveled” assertions, it’s worth asking how those figures were derived. The 1,518-mile average in the 2001 Iowa State study, for instance, looks rather precise. But it’s based on 28 particular items, all produce, arriving at the Chicago Terminal Market. The mileage figure was calculated by using mapquest.com to plot the distance between Chicago and a city located at the center of whatever state the produce originated.4

Is “average food item” a useful concept, as when people say something like “The average food item travels more than 1,500 miles”? In another Iowa State study in 1998, distances traveled ranged from 233 miles for pumpkins to 2,143 miles for grapes.5 The 1,518-mile figure in the 2001 study was an estimate not of the distance the “average food item” took to reach consumers, but the distance traveled by produce arriving in Iowa via the “conventional system.” Remember that distances for food acquired through local and regional systems were shorter, but were not part of the 1,518-mile calculation.

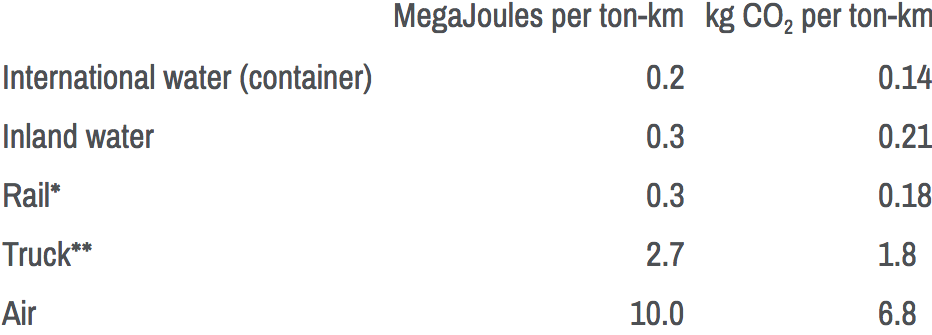

How far food travels may be less important than how it travels. A National Sustainable Agriculture Information Service article notes that “A food item traveling a short distance may produce more CO2 than an item with high food miles, depending on how it is transported.”6 Here is one British comparison of energy use and emissions per ton-km:7

* Varies depending on whether diesel or electric is used

** Varies depending on size and type of truck, power source

“Take the case of the well-traveled Idaho potato and its closer-to-home cousin from Maine,” writes Deborah Zabarenko. “For a consumer on the US East Coast, the Maine potato seems the winner in the local food derby. But Maine potatoes get to market by long-haul truck while Idaho potatoes go by train. So they have a smaller carbon footprint even with a larger number of food miles.”8

By one calculation, the average distance traveled by food between 1997 and 2004 increased by 25 percent due to globalization, but associated greenhouse gas emissions increased by only 5 percent, because of the greater efficiency of ocean shipping.9

As noted above, vehicle size matters. In the 2001 Iowa State study, the “local” food system required more energy and emitted more CO2 than the regional system because the trucks supplying the former had a smaller capacity, and therefore required more trips to deliver the same amount of produce.10

How food is grown may also be more important than how far it travels. A study by Swedish researcher Annika Carlsson-Kanyama concluded that it made more sense for Swedes concerned about greenhouse gas emissions to buy tomatoes from Spain than tomatoes from Sweden because the former were grown in open fields, while the latter were grown in greenhouses heated with fossil fuels.11 Under conditions of climate change, of course, that situation might change.

Christopher L. Weber and H. Scott Matthews of Carnegie Mellon University, writing in Environmental Science and Technology, calculated that transportation as a whole accounts for just 11 percent of the greenhouse gas emissions associated with household food. Wholesaling and retailing are responsible for 5 percent. The vast majority—83 percent—occurs during the production phase. As one way to put this in perspective, Weber and Matthews suggested that shifting less than one day per week’s worth of calories from red meat and dairy products to chicken, fish, eggs, or a vegetable-based diet would produce a greenhouse gas reduction that is equivalent to achieving an unrealistic zero food miles.12

None of this is to suggest that there are not excellent reasons for buying locally. Local food frequently has advantages of freshness, better taste, and less processing. Buying closer to home supports local farmers and keeps money in the community. Purchasers know where their food comes from and often know the farmer who raised it. A resilient local food system is insurance against disruption from a variety of factors, including climate change.

So, do food miles matter? They can be a convenient shorthand, as Sarah DeWeerdt affirmed, as long as we remember that they are a shorthand, and not the whole story when it comes to understanding our food system.